- Max Waldron

- Posts

- Avoiding Common Pitfalls in Exercise Selection

Avoiding Common Pitfalls in Exercise Selection

Make sure you're not a living, breathing example of the Dunning-Krueger Effect

Coach,

Roughly 15 years ago, when I really got into training and realised I wanted it to be my career, I got to a point where I was obsessed. I had dropped out of University after enrolling in a commerce degree, had saved as much money as I could in order to go overseas from working dead end jobs, and was backpacking through Europe.

I had a Nintendo DS on the trip, and I used it for two purposes. I would occasionally play Zelda, but more frequently I would connect to the WIFI at hostels and read blog articles and post on internet forums. This was before social media had really entered the training space - you had to actively look for information it wasn’t shoved in your face 24/7 the way that it is now.

I was starving for information and the more blogs I read, the more I wanted to read. While on the one hand this gave me a significant head start when I finally returned home and enrolled in a Sport Science degree, I realised fairly quickly that I couldn’t keep that pace up, especially once I began actually coaching people.

Today is far worse because you can follow thousands of coaches on Instagram and get an astounding amount of information in 15 minutes. This has a potential upside, but also a very real downside. Picture this: a fancy exercise that looks cool, so you watch and save it, maybe you give it a try and it makes it’s way into your programming for clients.

Here’s the thing all good coaches know - every exercise can be good or bad depending on the variables. That’s not the point of this article. Whether it’s good or bad doesn’t matter because you have zero context. It’s just an exercise. The answers to the real questions of who, what, when, why - are up in the air.

You don’t know common technique flaws or cues to fix those flaws from an Instagram reel; you just know how some dude on the ‘gram looked and maybe how you felt doing it. Then you see multiple techniques within a small sample of clients, and you’re not sure how to fix them. You try to fix them, and some get better and some get worse. And then, one of your clients or another coach asks you “why are you doing that?”.

In my mind, the main reason everybody squats, deadlifts, bench presses, lunges, jumps, sprints etc is because the coaches who mentored us performed thousands of repetitions, learned from their own mentors who coached thousands of repetitions. Because of this our mentors when teaching us the movements also taught us what to look for, and we have now coached thousands of repetitions of our own.

We know what to look for; we can spot it in a nanosecond. We know a dozen cues to fix each mistake. And because we’re always coaching these moves, we keep coming up with new cues to help clients in new ways.

Some of my coaches and I have been coaching together for nearly five years, which is a lot of time on the gym floor. It’s not at all uncommon for me to see an issue with a clients form during an exercise and for one of my coaches to call it out before I get there. The exact same cue. We’re watching the same thing and seeing the same thing, and we’re using the same cues - because they work.

However, I’ll often get a question from a younger coach and the answer seems obvious to me. These coaches haven’t had the same floor time, so they’re not be seeing the same thing I do, because they’re not looking at the same thing. This is where I realise I need to be a better coach, not just to our clients, but also to other coaches because that’s what I was fortunate to receive from my mentors.

So how can we avoid common pitfalls with exercise selection and progression?

If we’re starting from the beginning, we look at all resistance training program design variables, straight from my old Exercise Physiology textbook (Powers & Howley for those playing at home).

Needs Analysis

Exercise Selection

Frequency

Exercise Order

Training Load and Repetitions

Volume

Rest Periods

I remember going through this at University and yawning (mostly because of the thousands of blogs I’d read that explained it already) but like all things we need a starting point. We then tweak and do what works for us as we gain more experience, we take what those who have done before us have given us and we make it our own.

Side note: I have found that coaches who aren’t willing to revisit these basic frameworks are often the very same coaches who fall into the trap of the Krueger Effect.

Typically this thought process starts when a new client comes on board, which means it could be at the start of a competitive season. For example’s sake, let’s say that is the case.

Needs analysis: What is the sport/goal? What have we learned by working with this sport/goal in the past? What are the common injuries associated with this sport/goal? Are there contraindicated exercises for this sport/goal?

What will be the exercises that I want to track progress with for the upper and lower body? How have we done these in the past? Is there a better option? How will we integrate new clients into this exercise? Does the client have a training background?

What is the goal for each of the phases throughout the year? Is the client ‘in season’? If yes, what days and times do they train? What days are more intense at training? What days and times actually work for the client to train with strength and conditioning, both in the gym and for speed/conditioning, if needed?

What works for their schedule, based on life commitments as well as our schedule, for days of the week and times of the day?

What other clients are in the gym at the same time as this client? Can I use the equipment I want to use? If not, is there a way to rearrange the training session/week to make it work better for all parties involved?

With all of the ‘gram stuff going around, I now think about the following questions to ask should I ever prescribe a new exercise that I see:

Can the movement be progressed/regressed? Different implement? Different pattern? Does this exercise fit into a progression track we already have in place, or is it separate?

Can you progress/regress intensity, speed, range of motion, etc.?

What am I looking to accomplish? Improved strength on main movements? Power? Mobility?

What have I done in the past to accomplish this? Is there something that I can coach better that may work just as well?

Can I explain why we are doing it to clients and coaches? If not, I’m full of shit.

Is the movement backed up? As I mentioned before, we do the movements we were taught and learned from others who have done them for decades. Research can be formal (published) or informal (anecdotal). Both types carry weight.

The Dunning Krueger Effect

Dunning-Krueger Effect

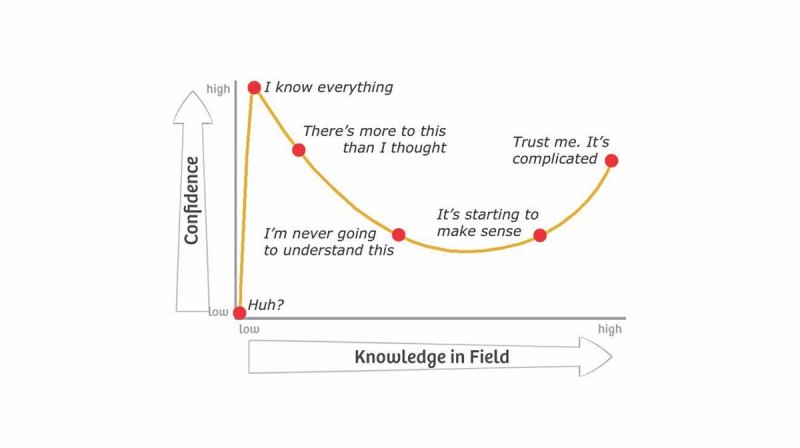

The last piece to this rant-ish article is the Dunning-Krueger Effect. The faster we can get coaches past the “I-know-everything” phase, the better we are as a whole.

However, as much as I wish I could slap coaches to achieve this, everybody has to get there on their own. Also, the “I-know-everything” coaches don’t know they’re at that level, so when they post some bullshit, they really do think they are at the far right end of that table above.

There’s nothing we can do except keep spreading the truth, keep sharing honest takes like this, keep liking the good ones in the field, and stop following, liking, and sharing the BS.

This is publicity game, and there’s no such thing as a good share or a bad share; a share is a share, and a follow is a follow.

Kill the bullshit by ignoring it.